Folke Bernadotte the mediator

Folke Bernadotte is known over much of the world for his White Buses’ operations and for his mission of good offices in the conflict in Palestine, where the latter mission also led to his tragic death. For a long time after his death there were relatively few stories about Folke Bernadotte’s life and efforts, and those in the foreground were by no means comprehensive. In recent years, new stories have emerged about Folke Bernadotte as a person and about his feats. Books dealing with his upbringing, early career and finally his tragic murder on 17 September 1948 have been published alongside books, articles and radio programmes that have focused more on two of his better-known international humanitarian efforts, the White Buses and the mission of good offices in Palestine. The perspective has been widened, and in some cases, criticism has even been levelled at, for example, how the operations were conducted. This exhibition aims to further widen the perspective of Folke Bernadotte, in particular in his role as leader and chief supervisor for the White Buses and in the mission as the UN’s official mediator and driving force behind the completely new type of organisation that was formed to try to resolve the conflict in Palestine.

Many have described Folke Bernadotte as a great humanist, with humour, warmth and an interest in people. He has also been described as perhaps slightly naive but with an almost unyielding willingness to do good as well as a relentless focus on achieving results.

In the work of the Peace Archives to digitise government documents and personal archives from Swedish peace efforts, we have regularly come into contact with Folke Bernadotte, partly through documentation from authorities and organisations, and partly through personal archives from a large number of people who worked with him. The picture of extremely complex and thoroughly challenging operations emerges together with the picture of Folke Bernadotte as primarily a good organiser and good leader with an ability to choose the right people to have around as well as to give support and a lot of space to people he worked with.

Folke Bernadotte and the White Buses

On 16 February 1945, an aircraft takes off from Bromma Airport in Stockholm. Its destination is Tempelhof in Berlin, and amongst the passengers onboard is Count Folke Bernadotte. His official mission is to inspect the small group of Swedish Red Cross staff who had arrived in Berlin earlier to support the Swedish Embassy in the repatriation of Swedish-born people from Germany. Bernadotte’s unofficial mission is to attempt to make contact with Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler and initiate negotiations on the release of all Scandinavians imprisoned in concentration camps.

The Norwegians and Danish had long held the idea of trying to repatriate Norwegian and Danish prisoners to their respective homelands. With the Allied offensive in the closing stages of the Second World War, there was also a considerably increased risk that the concentration camps would become part of the war zone. The developments added urgency to the situation and the plans had to be implemented without delay. Despite having been neutral throughout the war, Sweden now received a request from the Norwegians and Danes as to whether it could take practical responsibility for carrying out a rescue operation. Sweden accepted, and appointing Folke Bernadotte to take charge of the operation was a natural choice. Around a year earlier, Bernadotte had been appointed Vice President of the Red Cross and had practical experience as liaison officer in two major prisoner of war exchanges in Gothenburg. His extensive personal contact network and experience from when he was responsible for the diplomatically sensitive internment of foreign soldiers who had entered Sweden by various means were also seen as assets.

The planning of the operation was based on two main approaches, on the one hand negotiations with the Nazis to secure the release of the prisoners, and on the other hand a medical and transport operation to take care of the repatriation transport on-site. In parallel with the negotiations, for which Folke Bernadotte had now travelled to Berlin to initiate, the military, also under the utmost secrecy, had started to organise the detachment to be placed under the command of the Red Cross.

Staff recruitment is started in Sweden and the logistic regiments start to educate and train the recruits, at the same time as all of the equipment and vehicles are prepared. Colonel Gottfrid Björck is appointed head of the ground forces and the town medical officer at the time in Norrköping, Gerhard Rundberg, is appointed delegate-general to the medical staff. During the night of 8 March, the order comes in that all buses shall be painted white with large Swedish flags and a red cross in order for allied aircraft to more easily identify the vehicles. This is how the White Buses were born.

On 9 and 10 March the transport departs for Germany. In the initial negotiations with the Germans, Sweden was allowed to send 250 persons to carry out the operation. In addition to the staff, the operation included 36 buses, 19 trucks, 7 passenger cars and 7 motorcycles, as well as food, fuel and spare parts to allow them to be completely self-sufficient for one month. The first stop was the Neuengamme concentration camp outside Hamburg.

On reaching Germany, the White Buses set up their headquarters at the Friedrichsruh castle outside Hamburg. Folke Bernadotte’s negotiations now lead to permission being granted to collect all Scandinavian prisoners into an assembly camp in Neuengamme. Sweden accepts but sees this only as a first step in the negotiations - in the next step, the intention is to negotiate for the prisoners to be released and transported to Sweden. However, the efforts to set up a separate Scandinavian group in the Neuengamme concentration camp under the leadership of the Red Cross are hampered by the local SS command, and demands are being made for guarantees. Colonel Gottfrid Björck is faced with the demand that the Swedish force should carry out transport of the camp’s existing prisoners to other camps in order to make space for the Scandinavians. The recognition that the entire rescue campaign is at risk, and with the knowledge of how badly treated the prisoners are in Nazi transport, Björck makes a difficult decision, and he confronts the Nazis on this point.

In mid-March, the White Buses begin a comprehensive operation to transport Scandinavian prisoners and at the end of March, the Swedish Red Cross finally takes over the separate section of Neuengamme to which the prisoners are transported. The first transport operations take place from the Sachsenhausen camp and several camps in southern Germany, then from a number of different camps throughout Germany.

The operation is actually scheduled to end at the beginning of April, and some of the force returns to Sweden. However, up until now it has only been possible to take a limited number of prisoners home to Sweden, while a larger number than expected are assembled. Instead of ending the operation, the efforts are intensified and enter a second phase. Even though half of the Swedish force returns home, it is covered by the arrival of the Danes who have substantial transport resources. Folke Bernadotte also raises the temperature of the negotiations when he realises that the Nazis and Himmler are under enormous pressure. After completing the transport operation from Theresienstadt to Neuengamme, as well as being allowed to transfer Danish prisoners to Denmark, Bernadotte meets Himmler for the last time. They meet in Lübeck, which until now has served as a hub in the transport operations and where the Church of Sweden and Countess Majlis von Eickstedt-Peterswaldt have organised the administration, food and sleeping arrangements. Bernadotte and Himmler meet during the night of 23 and 24 April, and Bernadotte succeeds in his original objective, he is now granted authorisation from Heinrich Himmler to transport whoever he wants and wherever he wants without any restrictions.

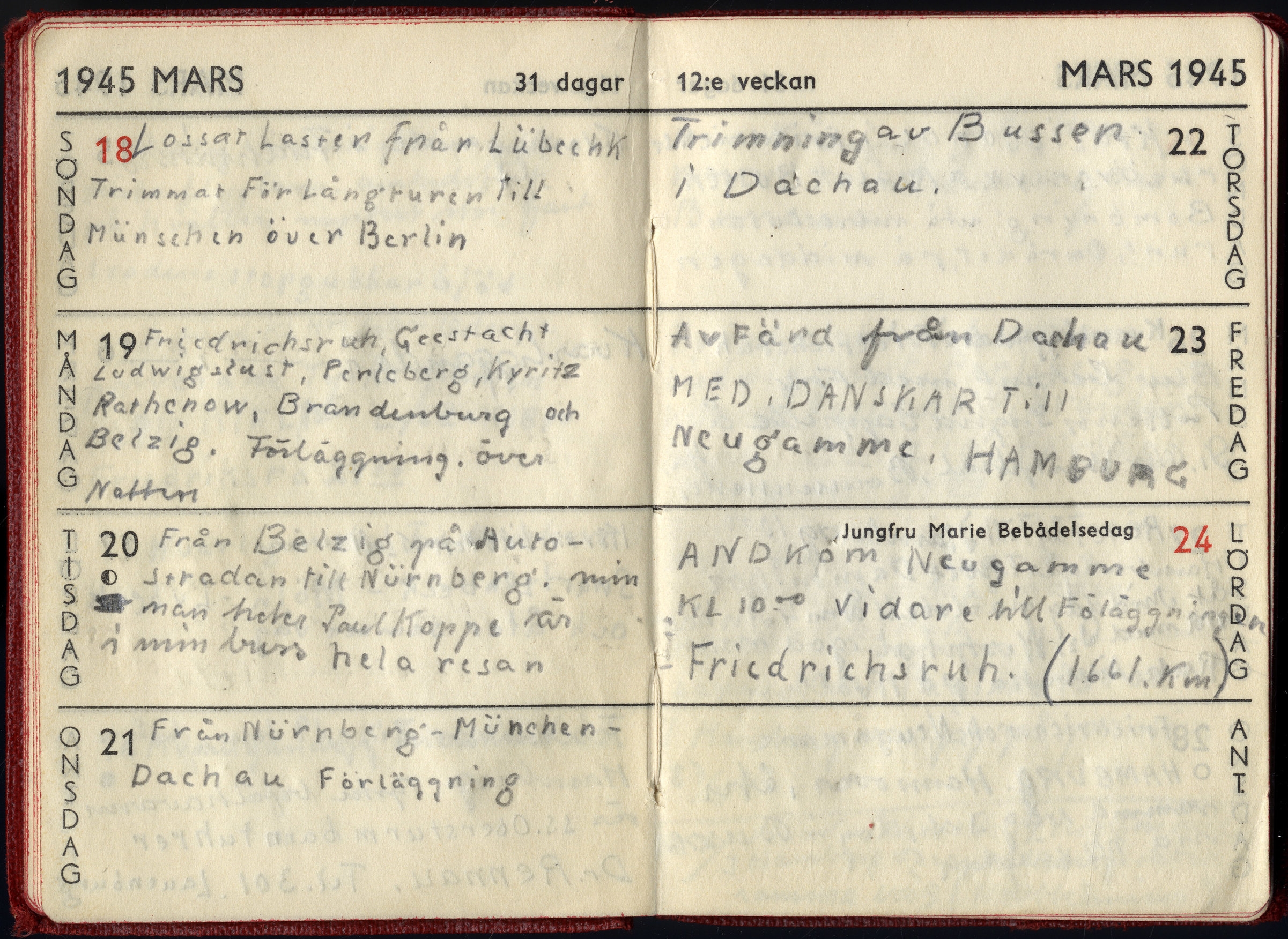

Pages from the calendar of Bertil Fröderberg, one of the drivers of the White Buses, March 1945

During the final stage of the operation, the White buses reach the Ravensbrück camp in northeastern Germany. At this point, the allied Russian troops are approaching, and it is important to save as many prisoners as possible. The buses are filled to bursting point and the transport route is direct to Denmark and then Sweden. Everything is done under constant shelling from low-flying Allied fighter aircraft. A group under the command of Lieutenant Hallqvist takes the road across Schwerin where the column suddenly comes under fire and the bullets break through the metal plate of the bus. Driver Erik Viggo Ringman is killed together with some of the women who were in the rear of the bus. Lieutenant Hallqvist and around fifteen others are wounded. During the coming day, several of the White Bus columns come under fire and some of the prisoners are killed or wounded. Despite the losses, the transport operation continues to Ravensbrück and almost a thousand prisoners can be saved. The headquarters in Friedrichsruh also come under fire and the whole of the old castle is bombed shortly after 24 April, fully evacuated. The detachment regroups and the last groups leave Lübeck on 28 April, finally arriving in Copenhagen on 1 May.

By the time the operation was completed, about 15,500 people could be saved from the concentration camps. Of these, about 7,800 were Scandinavians and they also managed to save 6,841 Polish citizens during the final stage of the operation. More than 4,000 of the rescued were Jewish and around 1,500 Swedish women and children with German citizenship could be taken home.

Germany surrenders on 7 May and the war in Europe is over.

Folke Bernadotte and the UN in Palestine

The end of the First World War and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire awaken the nationalist dreams of the different peoples of Palestine to life. Following negotiations, the newly formed League of Nations (LN) took a decision in April 1920 on a mandate for the state of Palestine, in which the rights of the different peoples should be observed. The United Kingdom has responsibility for the security of the Palestinian mandate and for the political, economic and administrative structure.

However, the conflicts in Palestine escalate and the genocide of Jews in Europe bestows greater dignity on the issue of a Jewish homeland. The dissatisfaction with the British administration also grows in both the Jewish and the Arab population. In 1947 the situation is so tense that the British begin to evacuate civilians and announce that they intend to leave the area when the mandate expires on 14 May 1948. The United Nations General Assembly (UN), formed after World War II as a successor to the LN, decides that the area of Palestine should instead be divided into an Arab and a Jewish part.

When the British mandate expires on 14 May 1948, the UN nominates the Swede Folke Bernadotte as mediator and he initiates a collaboration with the Truce Commission for Palestine formed three weeks earlier. The same day as the British mandate expires, the Jewish population proclaims the state of Israel and the next day, the newly-proclaimed state is invaded by a coalition consisting of the neighbouring countries of Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria.

All-out war is now being waged between the newly-proclaimed state of Israel and its neighbours. On 29 May 1948, the UN Security Council adopts Resolution 50 (UNSCR) calling on the conflicting parties to cease fire. The UN also takes the decision to urge its member states to send “a sufficient number of military observers”. When Folke Bernadotte arrives in Palestine, the situation is urgent and in addition to the assignments he takes over from the Truce Commission for Palestine, he decides on an improvised observer force. He requests the rapid engagement of five Swedish colonels as his staff and 21 officers each from the United States, France and Belgium.

On 11 June 1948, a first ceasefire begins and the improvised observer force begins its work. However, the first ceasefire only lasts for four weeks, and in the connection with fighting flaring up again on 9 July, the observer force is pulled back. The UN calls for a new, more permanent, ceasefire and in connection with it coming into force on 15 July, a new observer force arrives. The new force initially consists of sixty observers, but will grow as the needs increase. During the autumn, the UN Security Council approves a more permanent structure for the observer force and the new organisation is called the United Nations Truce Supervision Organisation (UNTSO).

During autumn 1948, the idea is that UN mediator Folke Bernadotte should present a new peace plan but on 17 September, only days before the plan is due to be presented, he is murdered together with French colonel André Sérot. The American diplomat Ralph Bunche, formerly Bernadotte’s adviser, takes over the work as UN mediator.

During 1949, bilateral peace agreements are negotiated between the conflicting parties and the UNTSO observer force changes over to monitoring the peace agreements, work that continues even today. From the outset, UNTSO was an unarmed military observer force, and its most important tools have instead been binoculars, report pads, all-wheel drive passenger cars and above all recurring meetings with the parties where the mediation mission has been institutionalised. The force has varied in size throughout the years, from as many as 572 (1948) to as few as 40 (1954). Today, the force consists of about 150 military observers, about 90 civilians and about 150 local employees. The limited size of the force has made it difficult to stop any violations, but UNTSO has still played an important role as mediator in the region.

First and foremost, the force has been important for allowing the UN to have a continuous presence in the area, but the force has also been an important support resource for other more comprehensive peacekeeping efforts in the region. Amongst other things, organisational support for UNEF I, in connection with the Suez crisis in 1956, and as support function for the UNIFIL operation in Lebanon in the 1970s. On the formation of UNEF II, in conjunction with the Yom Kippur War, the Head of UNTSO was appointed Head of UNEF II, and in 1960, the then Chief of Staff in UNTSO, Swedish General Carl C:son von Horn, was appointed Force Commander for the ONUC operation in the Congo.

Up until today, more than 1,000 Swedes have served as observers in UNTSO. Including Folke Bernadotte, four Swedes have died during their operations in UNTSO, of which three died as a result of direct hostilities. Folke Bernadotte and André Sérot became the first in history to die in a UN operation.