"A soldier is TOUGHER"

“The unlikely UN soldier in Katanga” is the title of a self-published book, by Erik Lindholm, which is based on his notes and diaries from his time at the 12th Swedish UN Battalion in the Congo, during the 60s. As the book reads: “He was, in his own view, the most unlikely UN soldier in the Swedish camp, a scrawny, crew-cut, sensitive kid from Umeå with dreams of becoming an actor, who suddenly found himself in an exciting and increasingly frightening world, where it was crucial to fit in and to survive.”

At 21 years of age, Erik Lindholm left for the Congo, to serve as a radio operator with the 12th Swedish UN Battalion. The year was 1961. Despite his initial hesitation, he became convinced that he had to go. Erik was very interested in the theatre and a member of a Shakespeare society. A large part of his account concerns the difficulties in uniting the two identities he felt were clashing, on the one hand a UN soldier, on the other hand, an actor.

The account is mainly based on his notebooks from the time, and centres thematically around the ambivalence mentioned above, an ambivalence which is expressed in various ways. He became friends with a local boy named Théos, a 16-year old with artistic interests, who later ends up in the refugee camp, which at the time is emerging around the Swedish UN military camp. This is one of the causes for the anxiety Eric feels, in part due to him becoming aware of how it is to live in Katanga and the Congo, in part due to some of his comrades being very critical of this friendship. In the beginning of the mission he feels like he is on a vacation trip, most of those in the Congo have a hard time taking it seriously, but the gravity of the situation enters their lives without mercy when Dag Hammarskjöld’s aircraft is shot down and the negotiations with the Katanga leader Tshombe come to a naught.

Below follow several quotes in the order they appear in Erik’s account. The idea is that these will depict Eric’s thoughts at the time, high as well as low.

“I am an UN solder in Congo. Radio operator at the Swedish Battalion in E/ville. I, who hated the conscription, who saw it as confinement and degradation, a necessary evil to endure without completely losing your self-confidence. When the guys caught the great Congo fever, I was the one who urged them not to, pictured all the dangers in Africa, war and disease, the heat, the alienation. Then, I became one of the few who applied. I found an application form that someone had dropped under one of the beds while I was cleaning the dormitory. It was a Saturday, and everyone was on leave, except me, who had been negligent in cleaning my locker. I read the word ‘Congo’ on the application form, and something exploded in my mind. What an adventure! The final challenge. The chance to see something I would never get the opportunity to see otherwise. ‘Congo’, it said, and Africa gave me the shivers in a way that made my hand shake when I filled out the form. A couple of weeks later I was accepted.”

“I am surrounded by the Congo. News in Swahili, Lingala, and French. Happy music with African Jazz, Kale-Roger sings about ‘Manuela’, and Nico describes a conference with Tshombe and his ministers in ‘Table Ronde’. The hours pass by, the switchboard is silent, and the homesickness grabs hold of me once again. Light summer nights in Umeå. The summer house, the cliffs, the sea. The Shakespeare society and all the friends, Kerstin and Siv, Walter, Maj-Lis, Barbro, Buntis, Margareta. Tours with Hamlet and the Folkunga Saga. The playfulness, the camaraderie, the fantasy. The dreams of a future as an actor.”

Photo: Bengt Lundberg

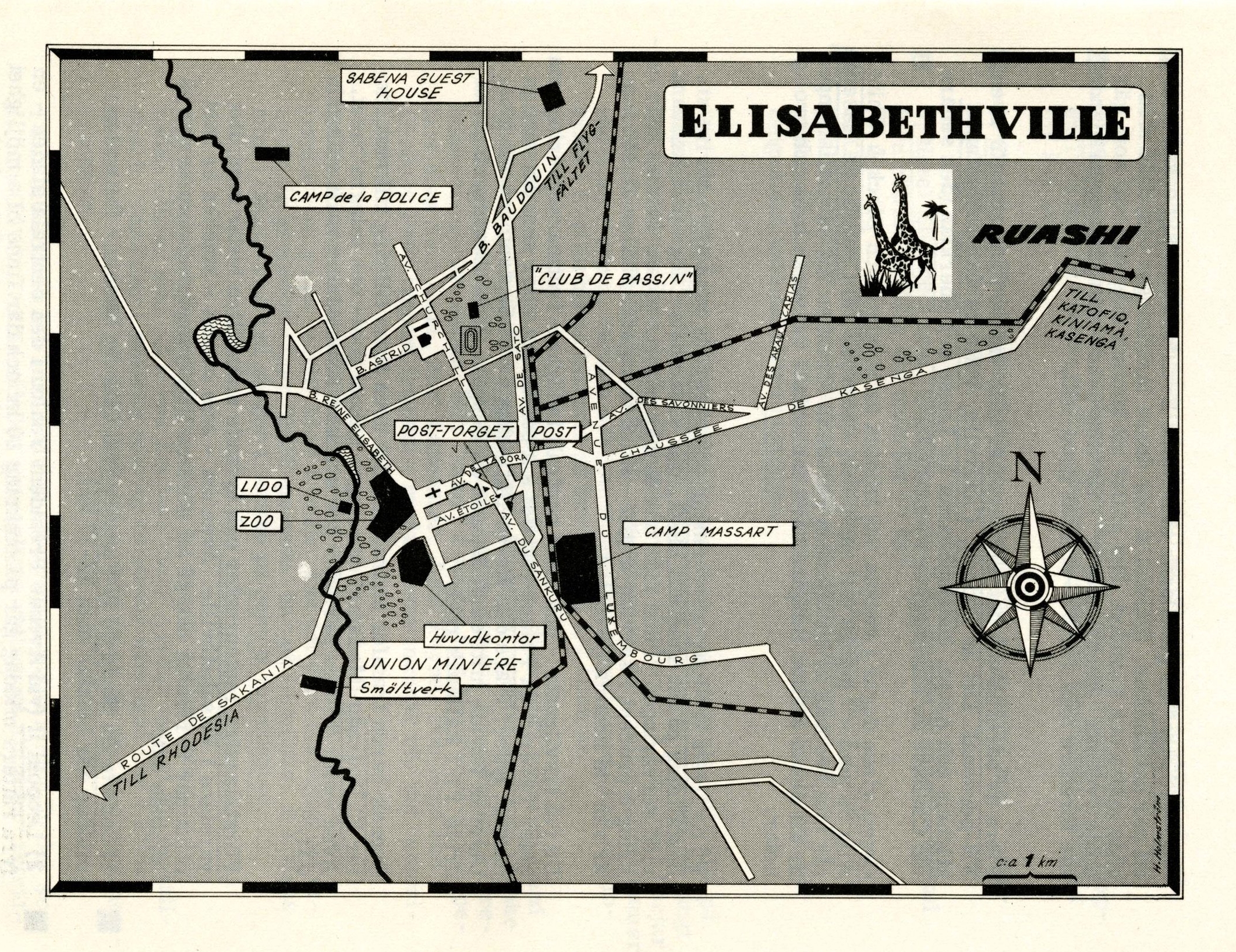

“Our free time in E/ville involves taking walks around the city with a camera or trips in trucks to the swimming pool at Lido, a restaurant. Sometimes we get to ride with the duty driver to a mining hole filled with water, which is an excellent lake for swimming where we can sunbathe, dive and relax from thoughts of how deceptive the calm is in E/ville. None of us have forgotten the pictures of the uprising at the airport last year, which were shown to us before we signed the contract in Strängnäs; pictures of an aggravated crowd, brandishing long, bloodied knives. No one has forgotten that the targets we practised shooting at with sub-machine guns represented humans.”

Photo: Bengt Lundberg

“Madame Tshombe and a women’s club have their annual party. We have walked among stands and carousels and mixed with the Katangese, seen a show of square dances, listened to Manhattan Brothers from Rhodesia, and spent a whole lot of money on games and shooting. But above all we have walked around, gazing at the black and mulatto girls of Katanga, to be able to brag about a conquest in the camp, though everyone of us knows that the girls of E/ville are almost unreachable, except in the brothels, which, although they are forbidden for us UN Swedes, constantly pull and attract.”

/…/He is back. Holds out a cigarette and lights it. Takes one for himself and takes a drag like you do when you’ve just started smoking.

“What's your name,” I ask.

“Théos. And you, sir?”

“Erik. You can say you. I am not used to ‘sir’.”

“It is difficult for me to say you to white people. I have no white friends, except those who go to my school, but they don’t speak too much to me.”

“Which school?”

“L’Institute International, a high school in town. We have both Belgians and Katangese students.

“Which subjects do you like?”

“All. Though, I like art the best.

“What would you like to be?”

“If there was an Art school. I would try to be an artist. Working with copper. Have you seen... Have you seen the theatre here in E/ville?”

“Yes.”

“Everything inside is made out of copper. I would like to do things like that.”

“And if you don´t become an artist?”

“Then I’ll become a soldier, I suppose. Like you.”

He has problems with the cigarette and laughs when he sees that I notice.

“I am not used to it, he says. I normally don’t smoke.”

“Neither do I. Only now and then.”

We throw the cigarettes in the fire

“It is no good to smoke. The lungs...”

“I know.”

He gives me a searching look.

“I think you’re too young to be a soldier.”

“Twenty, I say. It’s enough.”

“Not the age. The face and the manner. A soldier is tougher.”

“Like you?”

He laughs again.

“As soldiers, we always have things to talk about which unite us, our opinion on the military police and the officers. Although we respect the commanding officers, above all Colonel Waern, Major Lindvall, and Major Forslund, but we despise the corporals and lieutenants who, by any means, will prove that they can give orders and rule us. I recognize their tone from when I was conscripted, sharp and loud, their way of demonstrating their power is the kind that foster spite instead of obedience. So, we drift toward the forbidden streets, filled with adrenaline from the fear of getting caught, but firmly decided to spite the authority. The excitement turns the trip into an adventure."

“We take a walk and go back to the mulatto woman, when we think the coast is clear. She says that she hasn’t been feeling well for a while, takes my hand and holds it against her neck and forehead, shows a facial rash she has contracted. We hastily say goodbye and hitch-hike back to the camp where we scrub ourselves hard with soap and water.

‘Now you’ve got syphilis, for sure,’ says Bertil, who also shook hands with Marguerite.

‘Sure,’ says Borgman, ‘it’s passed on by nothing more than a handshake.’

He tries to joke our fears away with some crude wisecracks, but only manage to make both himself and us jittery. We wash once again and promise by everything holy that we’ll never again touch a prostitute.”

“Colonel Waern speaks to the staff company.

‘I want to remind you that this is no tourist trip,’ he says. ‘We are in a country where the situation can change very quickly, and where two and two does´t always make four.’

Once again, we understand, just as in the first days in the Congo, that the UN service is for real, and that everything we have learned here and during our training in Strängnäs, soon will be vital for us and the whole UN presence in the Congo. Waern talks about morale and attitudes.

Colonel Jonas Waern Photo: Lars-Erik Widegren

‘We live in a country in crisis, a country that might be hard to understand. With people, who are different. Remember one thing. They are called Congolese or Katangese, not “hatchets” or other derogative words you can hear among UN Swedes. We are in their country and are obliged to respect them. IS THAT CLEAR?’

‘You´ll probably have to get it together now,’ someone said after the speech, ‘if you are to come back home alive.’

Everyone was affected. And still. The guys who managed the switchboard when we came and gave us instructions, said that their morale reached rock bottom after a couple of months in Congo.

‘You lose your bearings, that’s the way it is. The only fun is to get drunk and take a hatchet chick for a ride in the bush. Watching with a flash-light in your hand, while your pals take her, one after the other.’

We listened and after a while, we understood that the guys just wanted to assert themselves in front of us newcomers. Like the others, I am drawn to the brothels. But I am still one of the few who haven’t dared to sleep with a prostitute. ‘Damn, that was disgusting,’ says the friends, after being the fourth or fifth man with the same girl, on a smelly mattress in some shed, but still, they are drawn back again and fight over the prophylactic tubes when they come back to the villa. I will remain in the Congo for six months. How am I supposed to be myself after my UN service? How many of my illusions will I lose? Sometimes I get so tired of the talk among us UN Swedes, the jargon about booze and girls, the bragging to assert one’s positions among the other guys. Only sometimes, after a match of table tennis or late at night, then we can talk about serious things. Of course there is one guy who is religious, with him there is none of the usual guys’ talk, everyone respects him. Levi, he is calm and secure, I wish I had some of his strength and that I didn’t become so unsure in front of the cynical ones. I might be too young for UN service, at least emotionally. I should have waited until I became tougher. My Shakespeare friends in Umeå must wonder! Maybe I’m acting through all of this, another role which will render applause if it is performed with feeling. Most of all I want to become an actor.”

Photo: Bengt Lundberg

“I want to believe in the idea of the UN. Sometimes, when I’m called ‘idealistic by other UN soldiers, it sounds like an insult. A lot of people are irritated that I associate with black people and move around freely in the city, that I don’t follow the pattern and am seen as an ‘outsider’, almost as a traitor. When I hear Åström (fictitious name) and the warrant officer discuss the black people and call them ‘bloody rabble’ or ‘animals’, I get out of the way in fear of getting involved in something that will make my time in the Swedish camp harder, but I curse my cowardliness sometimes and wish I could speak up and say what I think, tell them that what I have seen in the black people in terms of sensitivity, humility, joy, weighs over all of the civilised veneer those superiors are so proud of, and tell them that with my black friends I’ve met the ‘intelligence of the heart’ which my mother always talked about when I was a kid. I have understood the meaning of that, here in the Congo.”

“Questions beset me every time I am alone at the switchboard. I write most of it down in my notebooks. Avoid discussions about black people with my friends. Do my best to fit in with the crowd. Since the conscription, the chatter about women and booze is deep-rooted, such jargon is routine, like everything else. Yet, there is a true solidarity between some of the guys, and I have some friends who let me be the one I am, without cynical quips. /.../Pucken understands me. We can talk about everything, from the usual guy's talk to thoughts about the meaning of everything, about space and how tiny humanity is. Pucken is the adventurer I admire, and I am, according to him, a pessimist who brood too much, although I joke my way through life and keep the spirits up for myself and others. Best of all, Pucken understands my friendship with Théos.”

“As soldiers we have been closely united during these days. The camaraderie among us is very good now. The Swedes have done amazingly well in combat and worked calmly and efficiently, never fired nervously and rashly. I’m grateful that I’m a radio operator and have been working in the camp during these days, not forced into combat like many others. When you see those, who are lying shell-shocked in the sickbay, you understand how lucky you are, not to be here as an infantry man. Today the UN flag is at half mast, for Hammarskjöld.”

“At the same time, almost against my will, I feel a tickle of excitement running through my whole body. At four, so we won´t be seen in the moonlight, I board the white tank and huddle up with all the infantry men, marksmen, and it finally it feels like our UN service has begun.”