Describing the horrors

“Was this concentration camp not planned and built as one of the communities where the slaves of the master race should even spend their future lives as unknown production numbers?”

When Gerhard Rundberg is contacted by Folke Bernadotte in early 1945 he is working as city physician in Norrköping. He accepts the assignment as delegate-general of the Red Cross mission of medical personnel to be included in White Buses rescue operation. One of his first tasks is to carry out an inspection of the concentration camp in Neuengamme.

The overall plan for the operation was to initially assemble all Scandinavian prisoners into one camp, Neuengamme outside Hamburg. The Swedish Red Cross would be responsible for running the Scandinavian part of the camp and transport to Denmark and Sweden would be carried out at a later stage. On 7 March, Rundberg is sent to the camp ahead of the setting up of the Scandinavian part. Rundberg summarises his experiences in a book “Report from Neuengamme” published shortly after returning to Sweden. In the report, Rundberg goes through every little detail about the Neuengamme camp, the transport operation, and largely everything he encounters, with the accuracy of a scientist. At an early stage, the SS tries to put a spanner in the works for Rundberg and does not allow him to visit the camp at first. On the other hand, both construction materials and tools shall be sent from Sweden so that the existing camp prisoners can build the Scandinavian part. The Swedes refuse and instead it is referred to a higher body to negotiate authorisation to enter the camp. On 29 March, Rundberg is granted access to the camp with some of his staff and on 30 March, Folke Bernadotte visits the camp.

Rundberg writes: “Was this concentration camp not planned and built as one of the communities where the slaves of the master race should even spend their future lives as unknown production numbers?” Furthermore, he describes congestion, lack of sanitary facilities, and rampant infections, typhoid fever, typhus and similar. Rundberg describes the food served as “not worthy of human dignity”, and malnutrition, vitamin deficiency and bowel disease were very common. In order to provide a quick overview of the camp, Rundberg sketched a map, which is inserted in “Report from Neuengamme”.

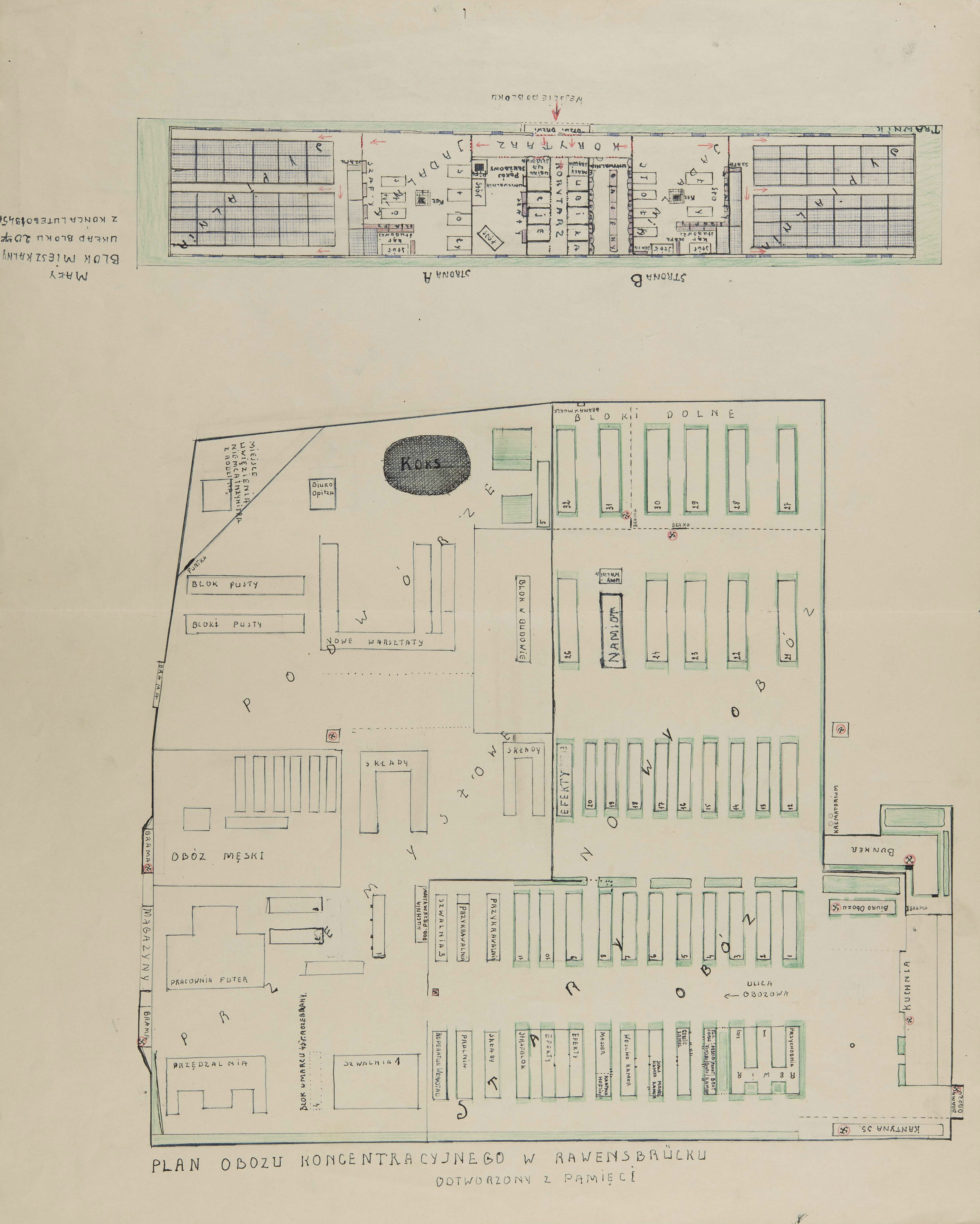

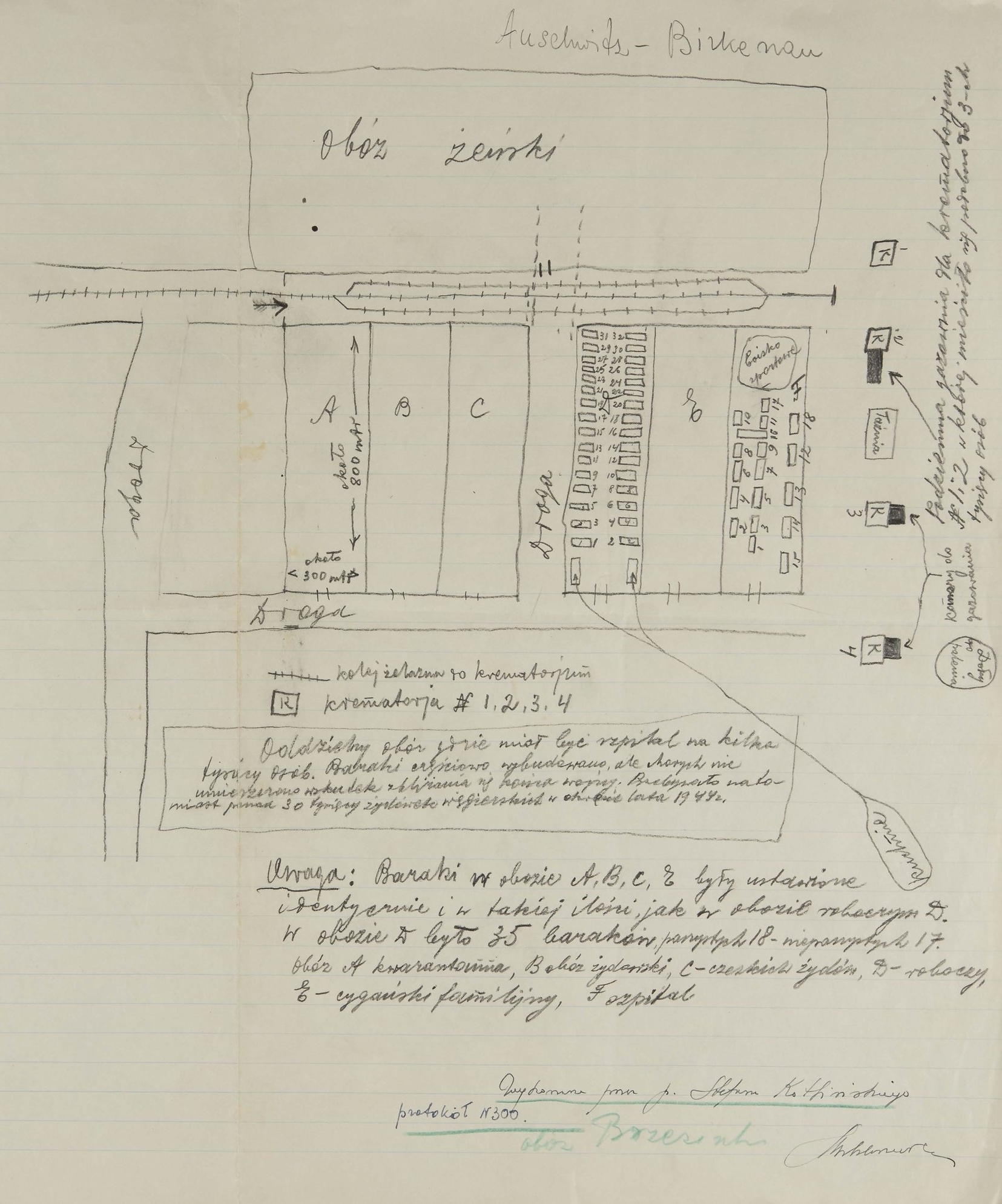

In 1945, at the time when the prisoners rescued from concentration camps start to arrive in Sweden, Zygmunt Lakocinski is a lecturer at Lund University. Since he speaks Polish, he helps to interpret for the Poles amongst the rescued prisoners. Lakocinski recognises the importance of documenting and saving everything released prisoners have to tell, such as for testimony in the Nuremberg trials. Together with historian Sture Bolin, he begins interviewing survivors as well as collecting and archiving material taken out of the concentration camps. Before the work ends in November 1946, 500 interviews have been conducted with the Polish survivors from the Ravensbrück camp. The activities that were financed by the Swedish state were given the name of Institute of Foreign Affairs’ Polish Working Group in Lund (sometimes also called the Polish Research Institute in Lund). The archive was sealed up to 1995, but today it is available digitally via Lund University. The material includes maps of a number of concentration camps and labour camps drawn by camp inmates. One of these maps is of the Auschwitz concentration camp, as Stefan Kotlinski remembered when he was interviewed in Sweden and a map of Ravensbrück, drawn from memory by another survivor. (See the illustrations above).

Read more about the rescued prisoners from Ravensbrück at Lund University Ravensbrück Archive “Voices from Ravensbrück”